Article - Library

Copyright

For permission or reproduction for this image, use the photographic application and guidelines here.

Summary

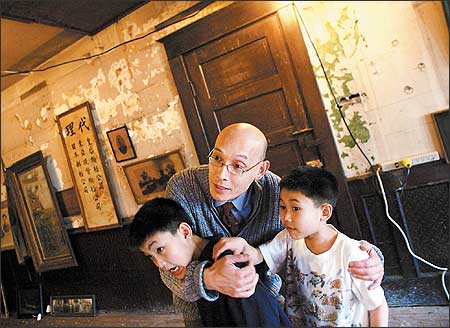

Ron Chew and his sons, Cian, 9, left, and Kino, 7, huddle as they hear noises from an old window shutter blowing outside one of the Kong Yick buildings yesterday. The building, constructed in 1910, was once a hotel for single men. The Wing Luke Asian Museum, where Chew works, plans to renovate it and turn it into a community showcase.

Old Chinatown attracts new money

Developer, museum step in to renovate four historic buildings

Tuesday, April 26, 2005

By VANESSA HO

SEATTLE POST-INTELLIGENCER REPORTER

At Wholesome Vegetasia, a ground-floor restaurant in Seattle's Chinatown, bamboo plants and green tea provide urban serenity. But on the floor right above it, rows of ruined windows scream urban decay.

At the Mon Hei Chinese bakery, it's the same thing: The downstairs bustles with customers buying pastries and coconut buns, while the upstairs sags with dark, vacant floors.

"You walk up King Street at night and it's dreary. There's no lights above. There's no hustle and bustle," said Bob Santos, a longtime International District activist.

Like many historic neighborhoods, Seattle's Chinatown has long suffered from blight and a split personality. Ground-level restaurants and shops attract chowhounds and curio seekers, but the skeletons of long-defunct hotels hover directly overhead. It's a phenomenon that dates back three decades.

But for the first time in years, a private developer is planning to invest heavily in the neighborhood, with massive renovations planned for three decrepit buildings. The developer, James Koh, hopes to start construction next month.

Also, the Wing Luke Asian Museum is moving into one of the 1910 Kong Yick buildings, with plans to turn the now-semi-vacant space into a sparkling community showcase.

The changes are a welcome relief, if not entirely embraced. Many in the International District are adopting a wait-and-see attitude about the plans.

"If nothing else, having (buildings) open will make a difference," said Sue Taoka, executive director of the Seattle Chinatown International District Preservation and Development Authority.

"We just hope it's the right kind of development making a difference in the neighborhood."

Others see the changes as just a start. Chinatown is a nationally registered historic district of just 12 blocks, but five of them are marred with at least one vacant, or semi-vacant, building.

"It's been a persistent problem for our neighborhood," said Tom Im, a neighborhood planner with Inter*Im, a community development association in the area. But after awhile, the shuttered buildings -- and the graffiti and drug dealing that bloom around them -- become "ingrained in people's psyches," he said.

In 2003, Koh bought three buildings in the heart of Chinatown:

# The 1911 Milwaukee Hotel, which is empty upstairs. Koh wants to turn this into 113 market-rate apartment units.

# The old Hong Kong restaurant building and Mar Hotel upstairs. Both sections are vacant. Koh wants to make this into commercial space with six top-floor apartments.

# The 1910 Alps Hotel, where $300 a month at the dilapidated front desk buys guests cramped quarters with no bathroom. Koh wants to convert this into 117 market-rate units.

"I want to see if we can make the place better, I guess," said Koh, who owns other properties around Seattle.

Like other hotels in the area, Koh's buildings once housed hundreds of Asian cannery and railroad workers in the early 20th century. But after 20 people died in the downtown Ozark Hotel fire in 1970, the city enacted strict fire codes for single-room occupancy hotels. Many owners couldn't afford the changes, and shuttered their buildings.

As the properties decayed, city officials and community developers tried to sway owners to fix them up. But most Chinatown owners have refused.

"We cannot afford," said Tony Wong, president of the Hip Sing Association, a social club that owns a four-story building on Fourth Avenue South. The lower floors hum with businesses and clicking mah-jongg tiles, but the upper floors are tattered and dark.

It would cost about $2.9 million to make the building livable, he said.

Other owners are elderly and unwilling to sell, go into debt or endure reams of paperwork for any of the government-funded loans available to help them. They also can't tear down the buildings, because the historic district that governs the neighborhood won't allow it.

Also, because immigrants often pooled money to build or buy buildings in the past, many properties still have multiple owners, making decisions difficult to orchestrate.

Curtis Dong, whose 75-year-old father co-owns the defunct 1908 Eclipse Hotel on South Weller Street, has talked to his cousins about reopening the building as a vibrant place to live and work. But his father -- and his father's elderly siblings who also own the building -- aren't interested. It's too much money and work, they say.

"We're talking about a really old generation," Dong said. "To them, they think, 'If we rehabilitate it, we'll never see the benefits.' They're from old school."

Over the years, the city has dangled carrots for property owners, to no avail. The Department of Housing announced a $10 million low-interest loan program four years ago, aimed mostly at vacant or earthquake-damaged buildings in the International District and Pioneer Square. So far, the only loan made was $7 million to the Cadillac Hotel in Pioneer Square.

The city's Office of Economic Development is now setting up a new $10 million loan pool to help projects in Southeast Seattle, the Central Area and the International District -- areas that haven't attracted much development. It's also looking into tax credits for developers in low-income areas.

They'll be a tough sell in Chinatown.

"What we're finding is the owners in the International District aren't enthusiastic about getting into a highly regulated fund source," said Bill Rumpf, the city's deputy housing director.

Housing officials estimate there are between 500 and 600 empty single-room occupancy units in the International District. For them, that's potential for hundreds of units of new housing, which the neighborhood badly needs.

"There's some hope," Taoka said. "As the next generation starts to take over the responsibility of these properties, they don't want to have on their conscience that they're slum landlords, or be the reason why the neighborhood is not thriving."

She just hopes none of the buildings collapse before then.

P-I reporter Vanessa Ho can be reached at 206-448-8003 or vanessaho@seattlepi.com

? 1998-2005 Seattle Post-Intelligencer

Title

Old Chinatown Attracts New Money

Author

Ho, Vanessa

Publisher

Seattle Post Intelligencer

Date

April 26, 2005

Object ID

1900.4808